PARIS: As Los Angeles firefighters battle remaining hotspots more than a week into deadly blazes, scientists and engineers hope growing availability of satellite data will help in the future.

Tech-focused groups are launching new orbiters as space launches get cheaper, while machine learning techniques will sift the torrent of information, fitting it into a wider picture of fire risk in a changing environment.

Satellites “can detect from space areas that are dry and prone to wildfire outbreaks…. actively flaming and smouldering fires, as well as burnt areas and smoke and trace gas emissions. We can learn from all these types of elements,” said Clement Albergel, head of actionable climate information at the European Space Agency.

Different satellites have different roles depending on their orbit and sensor payload.

Low Earth orbit (LEO) is generally less than 1,000 kilometres above the surface — compared with up to 14 km for an airliner. Satellites here offer high-resolution ground images, but see any given point only briefly as they sweep around the planet.

Geostationary satellites orbit at around 36,000 km, remaining over the same area on the Earth’s surface — allowing for continuous observation but usually at much lower resolution.

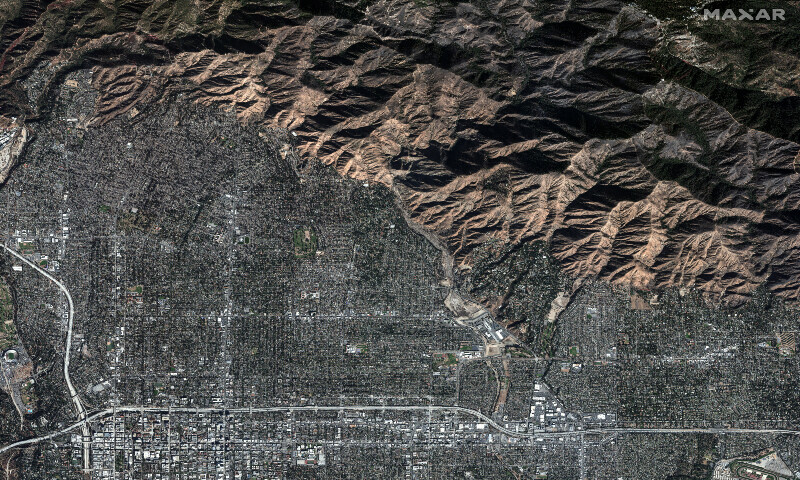

As climate change brings growing numbers of wildfires encroaching on human-inhabited areas, that resolution can be crucial. In Los Angeles, “there are satellite observations, but it’s very hard to determine — is it my house that’s on fire? Where exactly is this?,” said WKID Solutions’ Natasha Stavros, a wildfire expert who has also worked at Nasa.

“Some people stay because they don’t really understand… that’s where this idea (that) we need more observations available comes from.”

‘More fire than we know’

Brian Collins, director of Colorado-based nonprofit Earth Fire Alliance, plans a new low-orbit satellite “constellation” to complement existing resources. It will sport a sensor with a resolution of five metres (16 feet), much finer than ESA’s current Sentinel-2 satellites that can see objects only 10 metres wide.

This means “we’re going to learn very quickly that there is more fire on the Earth than we know about today, we’re going to find very small fires,” Collins predicted.

EFA aims to launch four satellites by the end of 2026, the first in just a few weeks, at a total cost of $53 million. That figure is a “drop in the bucket” against the property damage and lives lost to wildfires, said Genevieve Biggs of the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation, which has financially supported EFA’s satellite project.

It would take the whole planned swarm of 55, costing a total $400 million, to reach Collins’ aim of imaging every point on Earth at least once every 20 minutes. Dozens of satellites in orbit could “both detect and track fires… at a cadence that allows decisions to be made on the ground,” Collins said.

Less grandiose efforts include Germany-based OroraTech, which on Tuesday launched the first of at least 14 shoebox-sized FOREST-3 “nanosatellites”.

Published in Dawn, January 19th, 2025

Leave a Reply