Despite five masterplans and countless promises, why does Pakistan’s economic hub still look like a city in disarray?

If you speak to an urban planner, they will tell you that the Karachi you see today is far from what was envisioned. They will reminisce about a city with trams gliding through bustling streets, elegant colonial architecture, vibrant town squares, and open spaces where parades and serenades once brought life to the city.

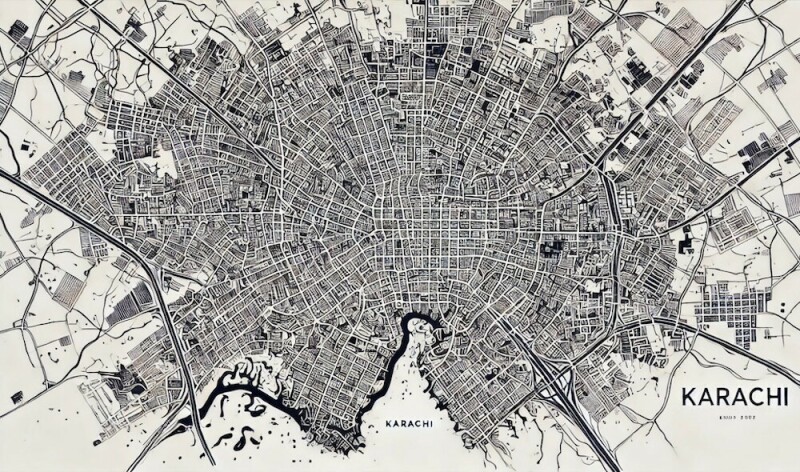

Today, these amenities are barely visible in the sprawling metropolis by the sea. Karachi, once the fabled ‘city of lights’, now battles gridlocked roads echoing with blaring horns, bazaars that sprawl chaotically under the shadow of unplanned structures and densely inhabited slums teeming at the seams. Yet, despite the chaos, the city remains a functional powerhouse — a melting pot of ethnicities and classes, contributing a staggering 25 per cent to the nation’s gross domestic product.

So, what went wrong?

Karachi’s urban journey is marked by five master plans, each a blueprint intended to guide its growth. According to urban planner Mansoor Raza, who serves as a board member of the Urban Resource Centre, a master plan is a preemptive measure to organise a city’s expansion. “When people live in a space, they inevitably shape it according to their needs, but without guidance, this can lead to haphazard development,” he explains.

At its core, a master plan aims to structure a city by carefully considering factors like population growth, transport, economy, recreation, and essential life events such as births and deaths. It identifies zones where these activities are feasible, ensuring the city grows cohesively with the authority to prevent or allow land use. Elements like geographic patterns, topography, demographics and the functions of the inhabitants are meticulously analysed to determine what belongs where.

In Karachi’s case, all of its master plans seem to have faltered. So what were they all about and why did they fail to shape the city as envisioned?

Karachi after partition

Said Woody Allen once: if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans. This idea, however, takes on a whole new dimension in a city like Karachi, where plans are seldom implemented and the joke seems to always be on the citizens.

While Karachi had several plans drafted by the British when they ruled the subcontinent, in this article we will only be talking about what happened in the port city after 1947.

Urban planner Arif Hasan, in his book Understanding Karachi, notes that after Partition, the city was divided into four distinct zones. The first comprised the old British and post-British suburbs, marked by narrow winding lanes, dense populations and bustling wholesale markets. This area was occupied by native merchants and the people who worked for them. It had a large number of mosques and Hindu temples where festivals were celebrated with fervour.

The second zone was Saddar Bazaar, a European-style shopping district with wide roads on a grid-iron plan. The residential area was dominated by Goans, Parsis and Europeans, who owned many of the businesses in the market. The missionary schools, churches, community halls and civic buildings were owned and operated by trusts belonging to Christians and Parsis. The surrounding areas were known as the European city where New Year and Easter were celebrated.

The third was the area between the two ‘cities’, comprising administrative and civic buildings, and educational institutes. Meanwhile the fourth was the area of Lyari and Machi Miani where the working class lived. A diesel-operated tramway linked these areas to each other and the port.

At the time, Karachi’s population stood at 450,000, of whom 61.2pc were Sindhi speaking, 6.3pc Urdu speaking, 51pc were Hindu and 42pc were Muslim.

By 1951, with the influx of people migrating from India to Pakistan, Karachi’s population ballooned to 1.37 million as most refugees ended up in the coastal city — the capital of Pakistan at that time.

The refugees occupied all open land and empty buildings left behind by the fleeing Hindus. They were multi-class and multi-ethnic, comprising intellectuals, artists, poets, performers and the working class — a majority of whom lived together within walking distance from Saddar Bazaar. In four years, Saddar became the city centre with a unique cosmopolitan culture and Karachi itself became a multi-class city.

However, as the city of lights was also the capital of the country, the government wanted to develop proper accommodation for its civil servants and incoming migrants from different cities. It thus initiated a planning process.

The M.R.V plan — 1952

This was the first attempt at a master plan for the city prepared by M.R.V, a Swedish firm. The plan envisaged a federal secretariat, legislative buildings and a large university around the independence square to the northeast of the city. It sought to rehabilitate the refugees in 10-storey-high blocks of flats along the Lyari corridor. A railway system for mass transit was envisioned and it was predicted that by the year 2000, the city’s population would rise to at least three million.

The plan was not implemented.

In 1953, student riots erupted supported by the citizens which led to the fall of multiple governments within a year. As a result, policymakers questioned the wisdom of having a university next to the capital’s administrative and legislative areas. They also questioned the appropriateness of having refugee colonies within the city.

Thus, a plan to develop the federal capital away from the city centre was conceived but neither of the plans were implemented.

Greater Karachi Resettlement Plan

In 1958, Gen Ayub Khan declared martial law and took a number of decisions that affected Karachi and its relationship with the rest of Pakistan. He decided to shift the capital to Islamabad. He also decided that refugees should leave the city and that the working-class people who were migrating to Karachi from other parts of the country should be discouraged from living within the city centre.

To achieve these goals, he hired a Greek planner, Doxiades, to prepare what is known as the Greater Karachi Resettlement Plan.

According to it, two satellite towns — Landhi-Korangi to the east and New Karachi to the north — were to be developed 25km away from the city centre.

Industrialists were offered incentives to invest here. Meanwhile, the refugee population and squatter settlement residents, who were forcibly moved to these places, were promised that they would find employment in these areas.

Like other plans, this too remained unenforced, as industrialisation was slow to develop. Moreover, the owners of the new core houses, developed by the government, refused to pay their instalments which were to be used to finance the continuation of the housing process. By 1964, the plan was abandoned.

Unlike the former, this plan had a number of repercussions on Karachi’s social, physical and economic fabric. Since the inner city refugee and squatter settlements were bulldozed and the new ones promised were left incomplete, it left behind an unmet demand for housing, resulting in the creation of squatter settlements on roads and along dry natural drainage channels run by middlemen, who are a powerful interest group to date.

As the poor left for areas away from the centre, the rich occupied its immediate vicinity. Speaking to Dawn.com, Hasan said that this caused much of Karachi’s ‘ethnic’ problems that exist today.

The Karachi Master Plan 1975-85

The failure of the Greater Karachi Resettlement Plan forced the government in the mid to late 60s to seek alternative solutions to the city’s housing and infrastructure problems.

For housing, they developed townships like Orangi and Baldia, which were at some distance from the main city and had no infrastructure. The state provided government transport and water supply by tankers.

Around these townships, squatter settlements started to develop and its residents made use of the facilities offered to the formal settlements. Soon, the squatter settlements became much larger than the formal ones. The state tolerated them as they were far from the main city.

Meanwhile, the bulk water supply, sewage and drainage facilities, transport sector, mass transit system and social sector infrastructure all required servicing so they could address the needs of the growing population.

Against the backdrop of this situation, in 1968, the government of Pakistan asked the United Nations Development Programme for assistance to prepare yet another master plan for the city of Karachi.

Thus came about the Karachi Master Plan 1975-1985, a landmark in the planning of the city.

In this book, Hasan noted that “by hindsight, one can say that it identified Karachi’s problems and growth trends with remarkable accuracy.”

It made plans for rational road networks, housing, upgrading katchi abadis, bulk water supply, transport, mass transit, warehousing and ecological issues. However, the plan yet again failed to achieve its goals.

The plots in the housing programme were too expensive for low-income residents. The loans were to be given on credit but most of the poor were non-creditworthy. The bulk water supply systems and roads developed were substandard in quality.

Moreover, no legal component was given to the plan. The reason for this, Hasan believes, was that legalisation would deprive the director-general of the Karachi Development Authority (KDA), the chief minister and other executives of the discretionary power that allowed them to bypass rules and regulations to sell and allot land. These powers were used by them to buy and reward political support and loyalty.

On the political front, Karachi went through various challenges as well.

First came the Bhutto era from 1972 to 1977 — the prime minister was a great supporter of the poor which led to the regularisation of katchi abadis. Regional cultures and languages made a comeback which led to Karachi, for the first time, becoming the capital of Sindh, where rural representatives dominated the assembly. A rural-urban quota for admissions to colleges and government services was introduced in Sindh to support the ‘underprivileged’ Sindhi-speaking population. All these steps created a distance between Karachi’s refugees and the latter.

Buttto saw Karachi as a cosmopolitan, international city. He planned five-star hotels, casinos, posh neighbourhoods, golf courses, and surfing and boating clubs to attract tourism. While only a few of these plans became a reality, they divided the city, in physical terms, between the rich and the poor.

In 1977, there was upheaval, which led to the takeover by the army.

The main concern for the army, during its decade-long rule which lasted from 1977-87, was to ensure that there was no major political movement from Sindh.

To ensure this, the ruling dispensation supported ethno-political organisations that had money and were often in conflict with each other. The provisions of the Karachi Master Plan were violated to provide land at throw-away prices to political opponents to purchase their loyalties. Encroachments on amenity plots were encouraged, and building contracts and permits were given in exchange for support of the regime’s policies.

No development activities were initiated; institutions collapsed and powerful interest lobbies were born. When the second generation of Karachi came of age, it wholly rejected the politics of their parents, who believed in a strong centre and aligned themselves with religious parties.

The 1987-97 decade was dominated by the Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM). The party dominated the politics of Karachi, becoming the king-maker at the provincial level. Their dominance forced the Sindhis to work in collaboration with the Urdu-speaking population. However, their representatives had little to no understanding of the administrative system which led to the collapse of state institutions and the promotion of corruption and nepotism.

Furthermore, to win political support, jobs were created in government sectors where they were not needed. For example, 14,500 employees were recruited for the Karachi Water and Sewage Board (KWSB) when only 6000 were required.

Ad hoc experiments like the division of Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC) into zonal councils and later regrouping them achieved nothing and instead weakened local government and institutions.

As the time for the Karachi Master Plan expired in 1985, a new plan was devised.

The Karachi Development Plan 2000

With the expiry of the 1975-1985 Karachi Master Plan, work on the Karachi Development Plan 2000 was commenced by the Karachi Development Authority with UNDP assistance. The plan was completed in 1990. An amount of Rs470m was spent on the preparation and hardware needs of the project like computers, and digital mapping equipment.

Essentially, the plan consisted of a computer model that would monitor developments in Karachi so that investments could be directed appropriately. It also comprised recommendations for planning and an institutional setup to be called the Karachi Division Physical Planning Agency (KDPPA), supported by a steering committee and an implementation board.

However, the monitoring and planning exercises could not be carried out without a constant supply of data for which no system was proposed by the plan. In addition, Karachi’s civic needs were being taken care of by powerful interest groups rather than by civic agencies. The plan did not study the interest groups; only a superficial attempt was made to do that. A legal cover was also not approved by the Steering Committee.

Due to these issues, the entire setup created by the Karachi Development Plan 2000 was ineffective and its provisions were violated.

If legal cover had been given to the plan, the use of Karachi’s land and real estate resources for political patronage would have halted. Hence, all successive governments that came after the development of this plan did not prioritise its implementation.

The absence of legal cover gave different departments the power to approve development plans without referring to the Master Plan department, leading to fragmented implementation of proposals and haphazard growth of the city.

For instance, the Karachi Building Control Authority took over the function of determining land use. They often made changes involving high-rise commercial development without taking in factors like urban development and environmental degradation leading the city into a state of chaos.

And yet, the city planners and politicians did not give up, but rather prepared to make Karachi’s fifth master plan.

Karachi Strategic Development Plan 2020

The work on the Karachi Strategic Development Plan 2020 (KDSP) began in August 2005 with an agreement between the city government and a local consultant, M/s ECIL, which offered the lowest bid of Rs57.621m. It was prepared by the Master Plan Group of Offices (MPGO) — CDGK in line with the vision of City Nazim Syed Mustafa Kamal, for making Karachi “a world-class city and an attractive economic centre with a decent life for Karachiites”.

Unlike other plans, KDSP 2020 was given legal status under Section 40 of the Sindh Local Government Ordinance 2001 (SLGO). The law made it mandatory for all agencies and stakeholders (federal, provincial and local governments) in Karachi to follow the plan when making their development strategies. It formulated a strategic framework and overall development direction and future pattern of the city over the next 13 years and beyond. However, it wasn’t until 2020 that a separate Master plan Authority was notified through a notification issued on Feb 18, 2020. The authority, however, remains on paper, pending cabinet approval.

The Public Accounts Committee has recently urged the Sindh government to legislate and establish a board of governors to oversee Karachi’s planning. Nevertheless, history suggests that this effort, too, may falter.

The preparation of the plan included a review of the existing conditions through socio-economic and land-use surveys. In addition, consultation and input from land-owning agencies, stakeholders, utility agencies, and technical committees comprising professional and subject experts were sought through a series of discussions.

When the plan was approved, Karachi was ranked in the top 10 largest cities in the world with a population of 15.1m expected to reach 27.5m by 2020. Around 40pc of Karachi’s population was afflicted with poverty.

Taking in the critique of the previous plans about the absence of a dominant private sector, the KDSP 2020 called for public-private partnerships to enhance the performance of service delivery institutions.

Woefully, the main critique of this plan was that it favoured the for-profit sector for the takeover of urban services and was a reflection of the neo-liberal economic mindset, where the market took precedence over basic human rights, which were treated as something that could be sold and bought.

Hasan wrote in his paper, ‘Land contestation in Karachi and the impact on housing and urban development’, that the plan aimed at creating residential and commercial development through urban renewal and high and medium-rise developments. New financial districts were also proposed on the Northern Bypass and along a road that cuts through mangrove marshes.

He pointed out that the lands opened up by the construction of Northern Bypass soon became a battle turf between the MQM, the PPP and the Awami National Party (ANP), representing the Pashtu-speaking population.

Owing to the constant conflicts and an unclear, constantly changing local government structure, none of the provisions of the plan were implemented. However, large-scale investments were made in the construction of signal-free roads, flyovers and underpasses, which did not improve traffic conditions during rush hour but rather increased the number of fatal accidents, especially of pedestrians and motorcyclists.

The coastal development programme consisting of high-end apartments, hotels, marinas and commercial plazas was initiated. But with resistance from fishermen’s organisations, environmentalists, important citizens from the elite of the city and civil society groups, which argued that the beaches would be lost to the people of Karachi as places of recreation and entertainment, the proposal too was shelved.

A new development plan for Karachi 2047 is being discussed. It remains to be seen whether that would take into consideration the 60pc of Karachi households that live and work in informal settlements. It would also have to address Karachi’s transport problems such as increasing vehicular traffic, the absence of effective public transport and the dilemma of unsafe roads for women. Moreover, it would have to incorporate the street and informal economy as well as the aspirations of the younger generation and resolve the battle over land contestation.

Hasan notes that the most important thing for the future of Karachi “is to create a sense of belonging of the people to the city”.

But will that happen, given Karachi’s previous experiences? It seems impossible, but is it?

It’s not impossible, it’s just mismanagement

“A city is a living thing, if its needs are unmet, it fulfils them itself,” remarked Hasan, reflecting on Karachi’s urban planning failures. He explained that all the plans were made after much delay and in the meantime, the city took its own measures to accommodate its growing population turning it into the mess it is today.

Seated behind his desk, surrounded by maps and books chronicling Karachi’s history, he criticised the top-down approach of previous plans. “If you don’t engage with the people, how can you plan for them?”

Similar sentiments were also echoed by Dr Noman Ahmed, chairperson of the NED University’s Architecture and Urban Planning Department: “It’s not impossible, it’s just mismanagement. If Islamabad’s master plan could be implemented, why not Karachi’s?”

Both urban planners reiterated that the main reason behind the failures has been the absence of legal cover, which both the bureaucracy and the politicians don’t feel important enough to make as it would curtail their powers to make decisions behind land use.

Hasan noted, “The main purpose of a master plan is to define land use; if it can’t do that, then how will it serve its purpose.” Among the city planners and authorities, he continued, there is an ‘anti-poor’ bias and a macho culture that needs to end.

Karachi is a culturally and ethnically diverse city where people from different classes have lived in harmony. Most Karachiites don’t expect an overnight overhaul, but they wish to live in a better Karachi — one that used to exist, wasn’t deprived of basic human rights and amenities, and was, most of all, a liveable space.

Header image created with generative AI

Leave a Reply